New Polymer Material That Can Harvest Solar Energy by Day and Release It at Night On Demand

Imagine a warm jumper that can release just enough heat to keep you warm and cozy in a cooler room without any need to fiddle the thermostat settings. Or, imagine a car windshield that can melt away the layer of ice on your car with the sun’s energy stored on it.

A team of MIT researchers have developed a new transparent polymer film that can harvest sunlight during the day, store the energy indefinitely, and release it later as heat, whenever it’s needed. The material could be applied to many different surfaces, such as clothing and glass.

“This work presents an exciting avenue for simultaneous energy harvesting and storage within a single material,” the University of Toronto’s Ted Sargent, who wasn’t involved in the research, told MIT News. “The approach is innovative and distinctive.”

The finding by MIT professor Jeffrey Grossman, postdoc David Zhitomirsky, and graduate student Eugene Cho, is described in a paper in the journal Advanced Energy Materials.

Even though the sun is a virtually unlimited source of energy, it’s only available during daylight, which is about half the time we need it. Therefore, in order for the sun to become a major source of power for human needs, there has to be an efficient way to save it up for use during night time and stormy days.

Most solutions have concentrated on storing and recovering solar energy as electricity or other forms. The new finding could provide a highly efficient method for storing the sun’s energy through a chemical storage system, which can retain the energy indefinitely in “a stable molecular configuration”, until it’s ready to be deployed, the researchers explain.

The key is an azobenzene molecule that can remain stable in either of two different configurations: charged and uncharged. When exposed to sunlight, the energy of the light kicks the molecules into their “charged” configuration, and they can stay that way for long periods. Then, when triggered by a very specific temperature or other stimulus, the molecules snap back to their original, ‘not charged’ state, giving off a burst of heat in the process.

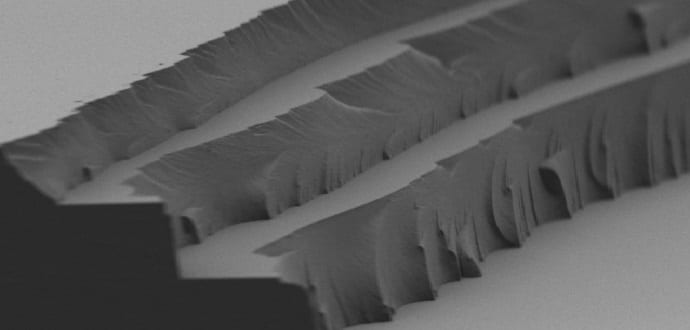

Such solar thermal fuels (STF) have been developed before, but this new method is the first based on a solid-state material (in this case a polymer) rather than a liquid, and that can make all the difference in terms of how it can be used. What’s more, it’s based on inexpensive materials and with widespread manufacturing in mind.

The material is also transparent, making it feasible for other applications, including as a defrosting device for vehicles windows. Many cars already have fine heating wires embedded in rear windows for that purpose, but they are inapplicable for the front windows as anything that blocks the view through the front window is forbidden by law. BMW, a sponsor of this research, is very interested in this potential application.

The team is continuing to work on improving the film’s properties, says Grossman. The material currently has a slight yellowish tinge, so the researchers are working on improving its transparency. And it can release a burst of about 10 degrees Celsius above the surrounding temperature—sufficient for the ice-melting application—but they are trying to boost that to 20 degrees.

Already, the system as it exists now might be a significant boon for electric cars, which devote so much energy to heating and de-icing that their driving ranges can drop by 30 percent in cold conditions. The new polymer could also significantly reduce electrical drain for heating and de-icing in electric cars, Grossman says.

“The approach is innovative and distinctive,” says Sargent, from the University of Toronto. “The research is a major advance towards the practical application of solid-state energy-storage/heat-release materials from both a scientific and engineering point of view.”

The research has been published in Advanced Energy Materials.